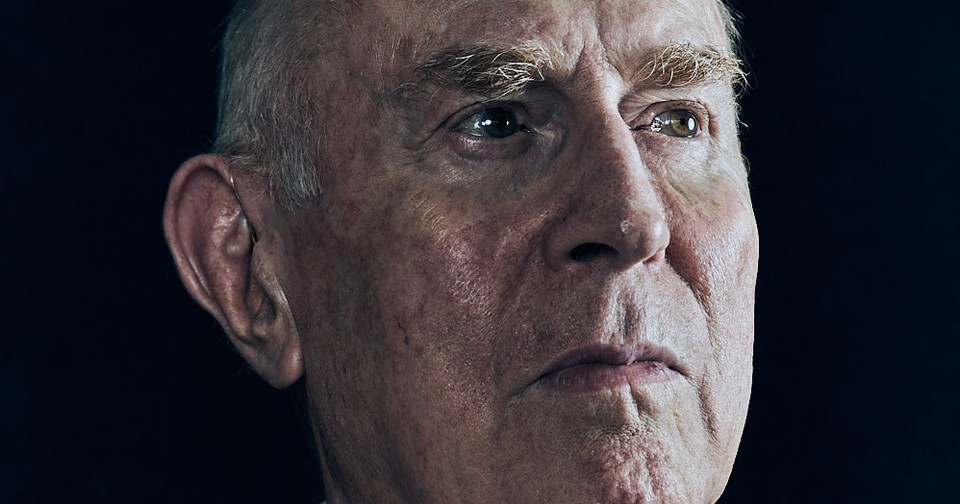

Doom lurks in each nook and cranny of Richard Rhodes’s house workplace. A framed {photograph} of three males in army fatigues hangs above his desk. They’re tightening straps on what first seem like two water heaters however are, the truth is, thermonuclear weapons. Resting towards a close-by wall is a black-and-white print depicting the primary billionth of a second after the detonation of an atomic bomb: a thousand-foot-tall ghostly amoeba. And above us, dangling from the ceiling just like the sword of Damocles, is a plastic mannequin of the Hindenburg.

Relying on the way you select to take a look at it, Rhodes’s workplace is both a shrine to awe-inspiring technological progress or a harsh reminder of its energy to incinerate us all within the blink of an eye fixed. Immediately, it feels just like the nexus of our cultural and technological universes. Rhodes is the 86-year-old creator of The Making of the Atomic Bomb, a Pulitzer Prize–successful e book that has develop into a form of holy textual content for a sure kind of AI researcher—specifically, the kind who believes their creations may need the ability to kill us all. On Friday afternoon, he’ll take his seat in a West Seattle theater and, like many different moviegoers, watch Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s summer time blockbuster in regards to the Manhattan Challenge. (The movie is just not primarily based on his e book, although he suspects his textual content served as a analysis support; he’s excited to see it anyway.)

I first encountered The Making of the Atomic Bomb in March, after I spoke with an AI researcher who stated he carts the doorstop-size e book round day by day. (It’s a reminder that his mandate is to push the bounds of technological progress, he defined—and a motivational device to work 17-hour days.) Since then, I’ve heard the e book talked about on podcasts and cited in conversations I’ve had with individuals who concern that synthetic intelligence will doom us all. “I do know tons of individuals engaged on AI coverage who’ve been studying Rhodes’s e book for inspiration,” Vox’s Dylan Matthews wrote not too long ago. A New York Occasions profile of the AI firm Anthropic notes that Rhodes’s e book is “common among the many firm’s staff,” a few of whom “in contrast themselves to modern-day Robert Oppenheimers.”

Like Oppenheimer earlier than them, many retailers of AI consider their creations may change the course of historical past, and they also wrestle with profound ethical issues. Whilst they construct the expertise, they fear about what’s going to occur if AI turns into smarter than people and goes rogue, a speculative risk that has morphed into an unshakable neurosis as generative-AI fashions absorb huge portions of knowledge and seem ever extra succesful. Greater than 40 years in the past, Rhodes got down to write the definitive account of one of the consequential achievements in human historical past. Immediately, it’s scrutinized like an instruction guide.

Rhodes isn’t a doomer himself, however he understands the parallels between the work at Los Alamos within the Forties and what’s taking place in Silicon Valley at the moment. “Oppenheimer talked rather a lot about how the bomb was each the peril and the hope,” Rhodes informed me—it may finish the battle whereas concurrently threatening to finish humanity. He has stated that AI is likely to be as transformative as nuclear power, and has watched with curiosity as Silicon Valley’s largest corporations have engaged in a frenzied competitors to construct and deploy it.

AI boosters and builders would little doubt take consolation in an argument Rhodes as soon as made, within the foreword to the Twenty fifth-anniversary version of his e book, that the invention of nuclear fission, and thereby the bomb, was inevitable. “To cease it, you’d have needed to cease physics,” he writes. This argument echoes within the rhetoric of bullish AI corporations and governments who see the expertise as a part of a worldwide informational arms race. Democratic nations can not pause or look ahead to legal guidelines to catch up, the logic goes, lest we lose out to China or another hostile energy.

That concept helps clarify why a technologist would assemble an AI system whilst they consider it may extinguish human life—and so does the epigraph within the first part of The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Right here Rhodes quotes Oppenheimer: “It’s a profound and crucial fact that the deep issues in science should not discovered as a result of they’re helpful; they’re discovered as a result of it was doable to seek out them.”

As a expertise author, I’ve spent a lot of my profession grappling with individuals who possess an impulse to construct, penalties be damned. I’m fascinated and confounded by the mindset I’ve noticed in AI founders and researchers who say they’re fearful of the very issues they’re actively working to convey into existence. I’ve struggled to sq. this persona trait with my very own inclinations: towards warning, towards a paralyzing obsession with matrices of unintended penalties. What’s it, I requested Rhodes. What’s the unifying high quality that possesses folks to open Pandora’s field? The query hung within the air, slightly below the dangling mannequin of the Hindenburg, as I imagined Rhodes flipping by way of a set of interviews and dog-eared biographies in his head.

He started to elucidate. Any nice scientist, “earlier than their twelfth yr,” he stated, has “some formative expertise that pushed them within the route they have been getting into, and made them determine they wished to undergo the grueling technique of studying arithmetic or science till they might push the boundaries.” Enrico Fermi, the inventor of the primary nuclear reactor and a chief architect of the atomic bomb, misplaced a beloved brother as an adolescent, and never lengthy after that, he grew obsessive about measuring and quantifying all areas of his life. “He may inform you what number of steps he’d walked down the road,” Rhodes stated. “He appeared a lot like somebody who present in numbers the form of certainty that he’d misplaced when he misplaced his brother.” As a 10-year-old, Leo Szilard had been so disturbed by a Hungarian epic in regards to the solar dying out that he grew fixated on rockets as a solution to save the planet, Rhodes stated—a quest that, ultimately, led him to find the nuclear chain response.

“It’s no coincidence that so most of the individuals who ended up within the bomb program have been Jews who had escaped from Nazi Germany,” he stated. “They’d seen what was taking place there, they have been throughout it, and so they knew it was horrible and terrifying and needed to be stopped.” Rhodes sees the shadows of his childhood in his personal work too, which was marked by bodily abuse and hunger by the hands of his stepmother: “It’s not shocking that every one my books are, in a roundabout way, about human violence and the way you cope with it, seeing as I’m an knowledgeable in that division.”

Maybe that is one other lesson in duality—within the grand scheme of issues, our nightmares and goals are of a chunk. If there’s a idea Rhodes desires AI researchers and founders to remove from The Making of the Atomic Bomb, it’s the notion of complementarity. That is an thought from quantum physics that the Nobel Prize–successful Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who, in response to Rhodes, traveled to Los Alamos to impart to Oppenheimer through the darkest days of the Manhattan Challenge. In very primary phrases, complementarity describes how objects have conflicting properties that can not be noticed on the identical time. The world accommodates multitudes.

Bohr, in response to Rhodes, developed a whole philosophical worldview from this commentary. It boils right down to the notion {that a} horrible weapon may concurrently be a beautiful device. “Bohr’s thought introduced hope to Los Alamos,” Rhodes stated. “He informed the physicists who have been involved about this weapon of mass destruction that this factor goes to vary this situation of battle, and thereby change the entire construction of worldwide politics. It may both finish the battle altogether or destroy the world. The previous gave them hope.”

The grand lesson, as Rhodes sees it, is that you could be construct an apocalyptic weapon that seems to be a flawed agent of precarious peace. However the reverse may be true: A device designed to perpetuate human flourishing may result in disaster. And so for Rhodes, the true concern concerning AI is solely that we’re on an undefined path, that we’re transferring too quick and creating methods which will work towards their supposed functions: devices of productiveness that find yourself destroying jobs; artificial media that finally blur the traces between human-made and machine-made, between truth and hallucination. “What’s most annoying about it’s how little time society must take in and adapt to it,” Rhodes stated of AI’s ascent.

On our method out of his workplace, Rhodes pauses to point out me a jar the scale of a movie canister with what appears to be like like some rocks in it. A pale typewritten label says Trinitite, the title for the residue scraped from the desert flooring in New Mexico after the Trinity nuclear-bomb check in July 1945. The blast was so scorching that it turned the sand to glass. “Fairly spooky, isn’t it?” Rhodes stated with a smile. It’s clear to me now why he retains these relics so shut. They’re the bodily manifestation of Bohr’s philosophy and the by way of line of a lot of Rhodes’s work—complementarity as inside design. A reminder that the enjoyment and the horror of each the pure world and the one we construct for ourselves is the truth that little or no behaves as we count on it to. Attempt as we could, we are able to’t observe all of it concurrently. It’s a reminder of the thrill and terror inherent within the unsolvable thriller that’s being alive.

Whenever you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.